Signature Limits

Lecturer: Stephen A. Butterfill

Minimal theory of mind has signature limits. These allow us to generate predictions to test conjectures about when mindreading involves minimal theory of mind.

Slides

- If the slides are not working, or you prefer them full screen, please try this link

Notes

A signature limit of a model is a set of predictions derivable from the model which are incorrect, and which are not predictions of other models under consideration.

Automatic belief-tracking in adults, and belief-tracking in infants, are both subject to signature limits associated with minimal theory of mind (Wang, Hadi, & Low, 2015; Low & Watts, 2013; Low, Drummond, Walmsley, & Wang, 2014; Mozuraitis, Chambers, & Daneman, 2015; Edwards & Low, 2017; Fizke, Butterfill, Loo, Reindl, & Rakoczy, 2017; Oktay-Gür, Schulz, & Rakoczy, 2018; Edwards & Low, 2017; Edwards & Low, 2019; contrast Scott, Richman, & Baillargeon, 2015).

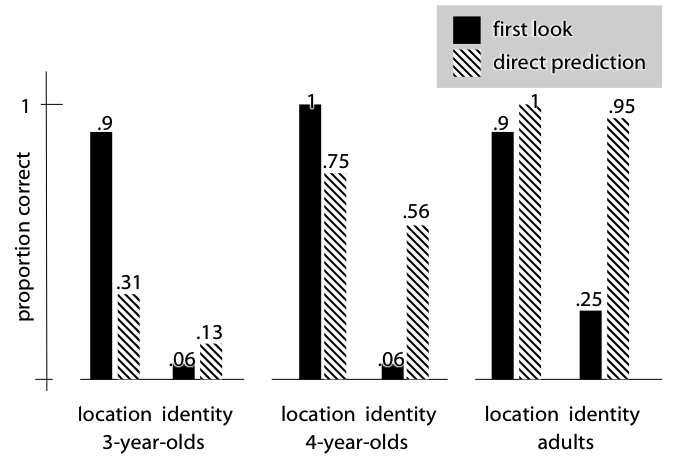

Figure: Signature limits illustrated. A response-by-content interaction that is robust across age-groups. Source: redrawn from Low & Watts (2013)

Figure: Signature limits illustrated. A response-by-content interaction that is robust across age-groups. Source: redrawn from Low & Watts (2013)

Objections

-

Low & Watts (2013) is replicable, but the paradigm involves confounds and so the results do not provide good evidence of belief tracking (Kulke, von Duhn, Schneider, & Rakoczy, 2018).1

-

Infant belief-tracking is not subject to the signature limit about identity (Scott et al., 2015).

-

‘the theoretical arguments offered […] are […] unconvincing, and […] the data can be explained in other terms’ (Carruthers, 2015; see also Carruthers, 2015a).

Glossary

References

Endnotes

-

Kulke et al. (2018) argue that although the paradigm from Low & Watts (2013) replicates, attempts to modify it to avoid confounding factors do not produce comparable results. In full:

‘There are two broad possibilities why only the Low and Watts (2013) paradigm was robustly replicated. One possibility is that this paradigm is particularly valid (perhaps because of lower processing demands or other relevant task factors) and therefore the most sensitive and suitable one to tap implicit theory of mind. The contrary possibility is that this task may be particularly prone to alternative explanations because of potential confounds’ (p. 8)

This motivated them to consider modified versions of the paradigm avoiding confounds, but:

‘the original pattern of belief-congruent looking could be reproduced only under conditions in which the belief congruency of the locations is confounded with additional factors, and therefore, this pattern might not reflect belief-based anticipation’ (p. 9)